|

The ups and downs of Amazon’s search for a second headquarter By Tony Favro, Senior Editor ON THIS PAGE: ||| The cut-throat battle between cities ||| Local economic growth is everything ||| |

|

FRONT PAGE About us   ON OTHER US PAGES The strengths and weaknesses of US cities during a pandemic MORE Homelessness in US cities: California is facing a crisis MORE Mayors of largest US cities (2020) MORE US mayoral elections November 2019 MORE US Mayors running for President MORE US cities are waking up to the harm done by trauma in childhood and adult life MORE In the US, cities lead in fighting poverty MORE Corrupt US mayors MORE Mass shootings in the USA MORE US mayors to protect DREAMers MORE America's undocumented immigrants pay billions in taxes MORE In the US, cities lead in fighting poverty MORE Spatial Planning and Development in the USA: Economic growth is of paramount importance MORE The ups and downs of Amazon’s search for a second headquarter MORE American public and mayors agree: Keep Obamacare, forget Trumpcare MORE More public involvement in law enforcement needed to ease strain between police and US communities MORE American cities save money by replacing obsolete urban infrastructure with green spaces MORE |

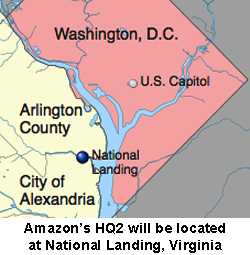

Initially some 238 North American Initially some 238 North Americancities pitched for Amazon’s HQ2 31 March 2019: When Amazon announced that the New York City borough of Queens would be the location of a major new investment by the company in November 2018, the news could reasonably have been expected to have been met with a shrug. After all, Amazon’s promised 25,000 new jobs over 20 years, or an average of 1,250 jobs per year, are a drop in a bucket in a City that is projected to add 170,000 jobs annually through 2024. Even if all the growth were concentrated in Queens (population 2.4 million), the new jobs and new residents could likely be accommodated and major disruptions avoided with proper planning. Instead, Amazon’s announcement provoked heated debate around issues of inequality and local control. While New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo and New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, who negotiated with Amazon, said they were “proud” and “thrilled”, respectively, to welcome Amazon, influential New York City Councilpersons and Queens’ residents were angered by being shut out of the economic development effort and fearful of rising housing costs and transport problems that might result. The $3 billion worth of state and local financial incentives—or $120,000 for each job Amazon promised to create—also raised concerns in a state and city that struggle to find adequate funds for quality health care and quality public education options for all children. When Amazon subsequently decided in February 2019 to withdraw its expansion plans for Queens and New York City in the face of local opposition, the finger pointing began. Mayor de Blasio blamed Amazon (“an abuse of corporate power”), Governor Cuomo blamed local politicians and their “narrow interests”, residents blamed New York State and New York City for being “secretive” in their deliberations with Amazon, and non-residents blamed Queens residents for their NIMBY (“not in my backyard”) attitude, which ended their chances of benefiting from the perceived economic opportunities. In fact, all of the finger pointers are right. And far from being a strictly local issue, Amazon’s competition for a second headquarters places the entire local economic development process in the United States under rare scrutiny.  The often cut-throat battle between cities The often cut-throat battle between citiesIn September 2017, Amazon issued a request for proposals for US and Canadian cities to compete for a major investment from the company. Amazon would invest US$5 billion in the chosen city and create up to 50,000 direct jobs over 20 years to build a “second headquarters” co-equal to its existing corporate headquarters in Seattle. Amazon’s requirements were few and straightforward. Basically, the company sought a new location in a North American metro area with a population of at least one million that was capable of attracting and retaining high tech workers. Although about 60 metro areas met these basic conditions, Amazon received proposals from 238 cities. Why would cities apply if they didn’t meet Amazon’s minimum requirements? “I just felt it was too big of a project not to take a shot,” said Mayor Chase Ritenauer of Lorain, Ohio (population 64,000). The opportunity for growth was irresistible to some cities, but also it seemed to be tacitly accepted that Amazon could and would change its own rules as the process unfolded (“disruption” from one perspective; “deception” from another). “Ineligibility is not a foregone conclusion, even if it looks that way on paper,” Mayor Nan Whaley of Dayton, Ohio (metro population 800,000) and other US mayors suggested on the CityLab website in defense of their cities’ below-threshold bids. And the cut-throat competition among communities was justified as the natural result of “free” competition. Toronto Mayor John Tory called the competition for among cities "the Olympics of bidding," a favorable comparison to the illustrious sporting event, and also a nod to the high stakes and visibility involved and the urgency to defeat, rather than cooperate with, other cities. Amazon’s Request for Proposals required applicants to “provide a summary of total incentives offered for the Project by the state/province and local community.” Since American states and Canadian provinces typically have a lot more money than cities, the RFP appeared directed primarily at states and provinces and their resources. “As this is a competitive Project, Amazon welcomes the opportunity to engage with you in the creation of an incentive package, real estate opportunities, and cost structure to encourage the company’s location of the Project in your state/province.” In other words, Amazon would work with states and provinces to get the maximum financial incentives it could, while avoiding local politics and local debates. A proposal from the Rochester and Buffalo metro areas of upstate New York State is illustrative of the process. Each city with its suburbs has a population of about 1.2 million. A private regional economic development agency from Rochester and its counterpart from Buffalo, with support from New York State, submitted a joint proposal on behalf of the two cities. Residents were not involved in the application process; nor, apparently, were most local political and business leaders. Neither the mayor of Rochester nor the mayor of Buffalo could explain why it made sense for two cities separated by about 130 kilometers of rural land to submit a joint application. Neither the details of the proposal (where the new Amazon facilities might be built in each metro area, how they would be linked, etc.) nor the financial incentives offered to the company by the state and local governments were revealed by the submitters of the proposal who cited the competitive nature of the process for their secrecy. The application process was similarly secretive throughout North America. Media coverage of the winner-take-all competition between cities was extensive and dramatic. The announcement of 20 “finalist” cities in 2018 dominated national and local media. While the media often tried, with limited success, to uncover the value of proposed public financial incentives in individual bids, the bulk of the coverage focused on the potential of the project to propel a region economically. "Amazon's HQ2 is the greatest economic development opportunity in a generation” asserted Maryland Governor Larry Hogan. There was little discussion of why Amazon, or any company, needs a second headquarters, or if Amazon would really create all the jobs it promised. There was little discussion of potential negative impacts on communities or individuals, or establishing parameters to balance community needs and those of Amazon. After nearly a year of reviewing the HQ2 proposals, Amazon announced plans to split its new, second headquarters between the Queens borough of New York and Arlington, Virginia, a suburb of Washington, DC, with each locality receiving 25,000 new jobs. When residents and local leaders in Queens protested, Amazon said its second headquarters would go to Virginia, which has embraced Amazon. Media reports suggest that Amazon is currently reconsidering New York City and has reopened negotiations with the state governor and New York City Mayor de Blasio. However the process eventually ends, Queens is a rare example of a US community nullifying the actions of political and business leaders regarding economic development and questioning their ability to operate essentially without restraint or even the necessary information regarding the consequences of their policy and business decisions.  Local economic growth is everything Local economic growth is everythingIn the United States, local governments have considerable autonomy and authority. They are responsible for providing such major services as public education to the university level, police and public safety, public health, and public transport. They also must pay for the services they provide. Local governments raise most of their money by taxing land and buildings. According to the US Census Bureau, local property taxes generate, on average, three-quarters of the revenues that local governments use to pay their bills. What this means is that local governments, to have enough money to pay the bills, must stimulate physical growth within their borders. They do this by competing with one another. Cities compete by reducing costs for developers in order to attract new developers and entice existing developers to build more. The competition for growth and development plays out on all scales in the US, not only at the Amazon level. For example, two neighboring municipalities may compete for a new shopping center by offering new roads, zoning changes, or financial incentives. Even neighborhoods within the same municipality often will compete with one another for a particular development. Since economic growth is crucial to any American city’s existence, it becomes a litmus test for the performance of local leaders and a magnet for media coverage. The success in office of mayors in tied to their success in attracting new development and new investment and in creating and retaining jobs. And local development is covered in the local media like sporting contests, with winners and losers. And sometimes the winners turn out to be losers: financial incentives are offered to businesses to locate in a particular city, which then has negative consequences. Development can bring high rents, traffic congestion, overcrowded schools, and overburdened infrastructure, which can stress municipal budgets already depleted to pay for the financial incentives used to attract the new development. There is a temptation for elected officials to favor developers over their constituents, and even engage in corrupt behavior. And new development can fray community ties, pitting neighbors who support development against neighbors who oppose development. Despite the potential failures, support for economic growth is primary in the US; everything else is secondary—sustainability, social and geographic equity, efficient land use, fairness, regional cooperation. And this explains why mayors of cities that were not chosen by Amazon for new investment were relatively sanguine. The competition for Amazon was a learning process for Kansas City Mayor Sly James, "It allowed us to talk about our city in a way that we hadn't been talking about on a consistent basis." And, according to Worcester, Massachusetts City Manager Ed Augustus, the bidding process may make his city more competitive in the future: “Just the discipline of having to organize a pitch has come in handy, and we've been able to use elements of it for other [economic development] efforts.” The competition for Amazon was not unique. Rather, it was an outsized version of what plays out every day in every American city. Follow @City_Mayors |