FRONT PAGE

About us

ON OTHER US PAGES

2020 US Census - Counting Americans

US mayors caught up in nation's culture war

Opinion: Trust and race in America

Opinion: Fighting racism in America

The guns of America

American mayors: Moral values in politics

Police killings of Black Americans

The strengths and weaknesses of US cities during a pandemic MORE

Homelessness in US cities: California is facing a crisis MORE

Mayors of largest US cities (2020) MORE

US mayoral elections November 2019 MORE

US Mayors running for President MORE

US cities are waking up to the harm done by trauma in childhood and adult life MORE

In the US, cities lead in fighting poverty MORE

Corrupt US mayors MORE

Mass shootings in the USA MORE

US mayors to protect DREAMers MORE

America's undocumented immigrants pay billions in taxes MORE

In the US, cities lead in fighting poverty MORE

Spatial Planning and Development in the USA:

Economic growth is of paramount importance MORE

The ups and downs of Amazon’s

search for a second headquarter MORE

American public and mayors agree:

Keep Obamacare, forget Trumpcare MORE

More public involvement in law

enforcement needed to ease strain

between police and US communities MORE

American cities save money

by replacing obsolete urban

infrastructure with green spaces MORE

|

|

No US federal government No US federal government

department is accountable

for reducing poverty

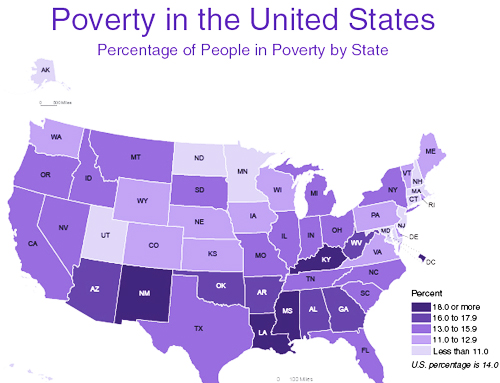

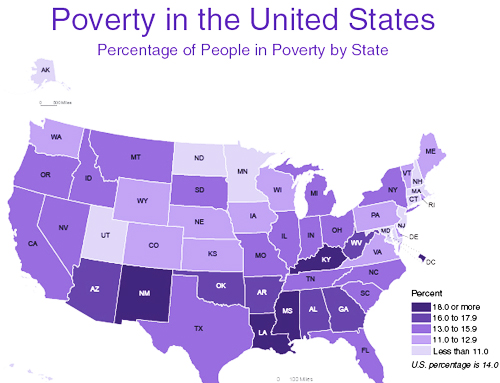

9 April 2019: Income inequality and social mobility generate intense discussion in the United States. A number of recent studies suggest that people at the bottom of the income ladder are unlikely to climb very far over the next twenty or more years; in fact, they will likely see the gap widen between them and the next rung of the ladder. Poverty in the US, it seems, is persistent, if not intractable.

Poverty is an official statistic measured by the US federal government—a series of income thresholds related to family size. A person or family that earns less than the poverty level is officially “poor” according to the federal government criteria.

Despite the official measurement, no single federal department is accountable for reducing poverty. In the US, there are federal agencies held to account for inflation rates, budget deficits, tax rates, crime rates, educational attainment scores, and other financial and social measures, but not poverty rates.

While poverty affects urban, suburban, and rural areas, income polarization is especially visible in cities. In most US cities, low-income residents are concentrated in certain neighborhoods.

The federal government and, to a lesser but important degree, the state governments control the key policy levers and have the revenue-raising capacity to significantly reduce poverty. There is only so much that cities can do when it comes to reducing poverty. Their hands are tied by both mandate and lack of resources. Yet, US cities have been compelled to take the lead when higher levels of government cut back on their programs and services, such as making it more difficult for the poor to get health insurance or reducing fair housing protections.

Large, midsize, and small cities, such as Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (population 1.6 million), Kansas City, Missouri (pop. 490,000), Providence, Rhode Island (pop. 180,000), Oswego, New York (pop. 17,000), and many others have opened anti-poverty offices. A few of these offices have existed since President Lyndon B. Johnson’s short-lived and failed War on Poverty initiative to eliminate poverty in 1964, but most have been established since the 2007 recession.

New York City’s anti-poverty New York City’s anti-poverty

program sets an example

Many cities are inspired by the success of New York City’s anti-poverty program. Between 2013 and 2016 the number of New Yorkers in poverty or near poverty (the percentage living below 150% of the city’s poverty threshold) decreased by 141,000, and the city is on pace to reach its target of moving 800,000 people out of poverty or near poverty by 2025.

New York City’s poverty rate in 2016, the most recent year for which there are data, was 19.5% and its near-poverty rate was 43.5% of all residents. By comparison, the poverty rate in Detroit was 34.5%; Cleveland, 33.1%; Bloomington, Indiana, 32.4%; Syracuse, New York, 32.1%; Philadelphia, 25.7%; Memphis, Tennessee, 24.6%; Columbus, Ohio, 19.8%; Boston, 18.7%; and Chicago, 18.6%. For US metro areas as a whole, 15.6% of all residents within central cities live below the poverty level versus 9.7% outside of cities.

New York City’s anti-poverty program is administered by the Mayor’s Office for Economic Opportunity. Philadelphia’s program is the responsibility of the municipality’s Office of Community Empowerment and Opportunity, and in Richmond, Virginia, the Office of Community Wealth Building. As the names suggest, cities are trying to reduce poverty by increasing opportunity. The names also acknowledge poverty’s broad and deep complexity.

Officially, poverty in the US is about people who earn less. In reality, it’s also about people who learn less, participate less, live at the margins, and are less visible to the mainstream, with neither power nor opportunity. In other words, poverty is a function of interlocking factors that are hard to disassemble.

A plethora of local programs

but no clear strategy

The US Conference of Mayors is a membership organization of about 1,500 US mayors. The USCM’s 2018 Policy Agenda identifies several priorities and related strategies to strengthen US cities. One policy priority is Create Equitable Communities to Increase Opportunity for All, and strategies to achieve this priority include: investing in inclusive neighborhoods, affordable housing, and community development; improving public education from pre-kindergarten through university; providing affordable and quality health care in every community and promoting an environment of health and well-being; and increasing equity and ensure civil and human rights.

All of these strategies can be found in local anti-poverty initiatives, as well initiatives such as: youth mentoring; job training; reducing unintentional pregnancies; raising minimum wages; providing universal basic income; increasing transport access, and many more.

It appears that cities are trying to identify needs and align resources with capabilities and the broad goal of poverty reduction. But there is also a sense that many of the decisions are ad hoc and clear poverty reduction strategies are lacking.

In Richmond, Virginia, the Mayor’s Order establishing an Anti-Poverty Commission states that the city “seeks to identify the root causes of poverty” but also charges the Commission with developing “strategies to address poverty that have demonstrable results for increasing employment and educational attainment, improving transportation, and enhancing health communities for Richmond residents.” In other words, a strategic direction is prescribed before root causes are known.

In a perfect world, root causes would be known and controllable and strategies would be designed to correct the deep root causes. Identifying the root causes of poverty is notoriously difficult: cause-and-effect relationships are uncertain; new needs continue to arise, as well as new opportunities; the pace of economic and social change can be unpredictable; results are similarly difficult to predict or measure due to dynamic contexts.

Stakeholders also bring diverse perspectives to the situation, making consensus on solutions a challenge. For example, many US mayors are trying to enlist local business leaders in poverty reduction efforts. The idea of a “triple bottom line”, in which it is possible for businesses to build in social considerations along with a healthy bottom line, seems crucial to anti-poverty initiatives. Cities alone will not be able to move a meaningful number of people out of poverty. And city governments and businesses have a mutual interest in a clean environment, healthy business climate, high-quality services, and cultural vibrancy.

However, engaging businesses in the more complex elements of poverty reduction can be challenging. For example, providing health insurance for entry-level employees is a cost which many employers seek to avoid, but its implications for long term employee and community health are far reaching. Committing to hiring at-risk or low-income workers often requires managers to assess the merits of potential employees based on competencies rather than high school diplomas or courses studied. It may even require hiring managers to overlook criminal records.

Questions that need to be asked

Given the complexity of poverty, mayors and cities must create an enabling environment that allows an anti-poverty program to adapt, and that means building in the ability to learn and adjust from the very beginning. *

What are some of the questions mayors and cities might ask as they undertake a poverty reduction initiative to make sure major challenges are addressed within a flexible framework?

• How can we meaningfully engage persons with lived experience of poverty in this work?

• With all the possible actions, how do we prioritize our work? What are essential, what are contingent on the essential actions, and what are nice-to-do?

• How can we raise awareness about the fact that poverty affects not just low-income households but everyone—through higher health care costs, social service costs, reduced business activity, and lack of productive contribution to the economy?

• How do we reach numeric targets when there may be lots of intermediate steps along the way?

• How do we justify investments in areas that may not show immediate results? For example, before poor people can get a job, they may need language training or childcare assistance; before welfare recipients can join the paid labor market, they may require educational and skills upgrading; before building affordable housing, it may be necessary to convince a given neighborhood that it won’t reduce property values.

• How and how often should we assess how we’re doing in our poverty reduction efforts?

• What factors should be considered major indicators of both intermediate and long-term success?

• How do we know if we are going off the rails or getting stuck on the track? How long do we stick with a given plan or program before we decide to shift gears and course correct?

• How can we acknowledge our successes along the way?

Conclusion

A powerful current of poverty reduction work is currently coursing through US cities. It’s too early to gauge results, as most initiatives are relatively new, and it’s often difficult to ascribe changes in poverty rates to any particular factor or program. Mayors and other stakeholders are thinking deeply about how best to proceed. They are trying to be strategic in their choices, a challenge given the wide range of areas in which to become involved. US mayors, residents, and other stakeholders are using their diverse experiences and mustering the courage to experiment, gather information, and then act accordingly to try to solve the complex problem of persistent poverty.

References and resources

The questions are adapted from Memo to the Mayors of Canada, a paper written by Sherri Torjman at the request of the Tamarack Institute as a follow-up to the National Poverty Summit held in Ottawa, Canada in May 2015

Selected resources:

F. Kayla, J. Semega, M. Kollar, U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60-263, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2017, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 2018.

M. Kearney, B. Harris, eds., Policies to Address Poverty in America, The Hamilton Project and The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, 2014.

Leadership for America: Mayors’ Agenda for the Future, United States Conference of Mayors, Washington, DC, 2018.

|

New York City’s anti-poverty

New York City’s anti-poverty