When launched in 2007, public reaction to the London Olympics logo was overwhelmingly negative

FRONT PAGE

Site Search

About us

London Olympics: Legacy

2012 Olympics: East London

Impact of 2012 Olympics

How London won the 2012 Olympics

Worldwide | Elections | North America | Latin America | Europe | Asia | Africa |

London Olympics: The Games will be a success

but doubts over their long-term legacy remain

By Jonas Schorr and Andrew Stevens

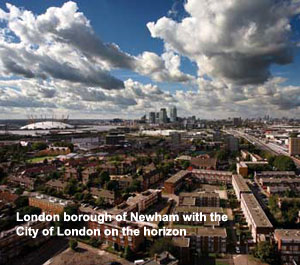

7 September 2011: For seven weeks, from 27 July to 9 September 2012, the Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games will take place in London. Since winning the 2005 bid against its competitors Paris, New York and Moscow, while promising that the 30th Olympiad would regenerate London’s East End, a lot has changed in England’s sixth-most deprived district of Newham and the surrounding areas of Stratford.

| Costs and investments | Green legacy | Venue legacy and re-use | Community engagement, tickets and safety | Fears and hopes |

Winning the bid to host the Summer Olympics might have been London’s last chance to open up an area, which has been continuously neglected since the onset of British industrialisation nearly 200 years ago. The area now populated by cranes erecting the last structures of the high-end, 2.5sq km (227-hectare) Olympic Park used to be deeply contaminated by poisonous chemicals, gasoline, lead or tar and a patchwork of landownership preventing any large-scale attempt for urban renewal. The London organisers are trying to rejoin the two sides of the Lower Lea river valley in order to link it to the rest of the city by adopting an inclusive and integrated approach.

Building a ‘smart city’, or rather a ‘smart district’ from scratch, where the local economy, politics and culture thrive, aided by a strong information technology infrastructure, good transport and built on a platform of ecological sustainability, is the ultimate vision at London City Hall. But it is easier written on paper than done, and there are few, if any, places that have achieved that in the past. One example could be the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona, where the legacy of the Olympic village near the waterfront helped revitalise a formerly deprived area.

Costs and investments

Costs and investments

In terms of ‘games readiness’, London already outperforms most of the Olympics’ prior hosts. According to the organisers and outside observers, the London Olympic site will be delivered ahead of time and under the revised budget of £9.3 billion (US$15bn). Construction started in May 2008 and a year before the opening ceremony, some 88 per cent of construction was completed according to the UK’s Sports and Olympics Minister, Hugh Robertson.

But not everything is so rosy in London. When it first won the bid in 2005 in a neck-and-neck race against Paris, it was based on government estimates that put the costs of the Games at about £3bn (US$5bn). In 2007, due to general cost underestimates and with private investors pulling out in light of the looming recession and financial crisis, the government was forced to step into the financial vacuum and more than tripled its original estimate to £9.3bn (US$15 bn).

The budget is made up from different income sources and totals the costs for staging the Games and building the necessary infrastructure in the London’s East End. The operational costs are budgeted at £2bn and are solely funded from the private sector by a combination of sponsorship, merchandising, ticketing and broadcast rights and managed through the London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games (LOCOG).

In contrast, £7.3bn of public government money are mainly being used to build the Olympic Park, increasing public infrastructure and environmentally rehabilitating the surrounding Lea Valley. According to the Olympic organisers, from every pound of public money spent, 75 pence is being invested into the regeneration of East London. Putting the budget in perspective, it appears almost modest compared to the alleged US$40bn spent on the 2008 Olympics in Beijing and is slightly below the costs of the 2004 Athens Games at US$16bn.

According to a study published by Visa Europe, one of the London Olympics’ sponsors, Britain will benefit from £750m (US$1.25bn) of consumer spending during the seven weeks of London’s Olympic and Paralympic Games next year. However, experience tells that predictions like these are hard to prove and often can only be evaluated years after a mega event is over and public interest has vanished.

Yet, there are more tangible numbers to hand that can give a glimpse on how London and British businesses have already benefited from the Olympics. A recent announcement made by the Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA), which oversees construction of the venues, stated that it had awarded contracts valued at more than £6bn with 98 per cent of which went to UK-based companies. In this regard, the 2012 Games indeed helped to safeguard British jobs, particularly in the construction industry and despite the generally gloomy economic outlook.

This said, there is little evidence to suggest that the expectations publicly set by Olympic officials and London’s mayor Boris Johnson, that the Games would lead to the creation of “tens of thousands” of new jobs, are anyhow justified. As the ODA reports, out of the about 10,000-plus people working on the Olympic Park and athletes’ village since April 2008, about a quarter were from London’s original five host boroughs and it has placed 1,500 people in work that were previously unemployed. Similarly, Adecco, a global HR leader and the company that provides LOCOG’s official recruitment services, disappoints regularly with no more than a handful of jobs on its official “Jobs for the Games” website.

Both cases suggest that the Olympic Games may only moderately stimulate the job market by creating new jobs for unemployed, but do have a significant impact in safeguarding employment in the construction industry thanks to large-scale government investments. In terms of private investment, the adjacent shopping mall built next to the Olympic park, which is expected to become Europe’s largest shopping complex with more than 300 shops, 14 theatre screens, hotels and office spaces, may provide additional jobs for up to 8,500 people.

Green legacy

Green legacy

Since its initial bid in 2003, London’s primary focus and message for the 2012 Olympics has been to create the “greenest ever Olympics”. It chose a handful of sustainability themes, trying to champion low carbon emissions, minimising waste, conserving biodiversity, and promoting diversity and healthy living. So far, one million cubic meters of contaminated soil have been cleaned, while an area of large parkland has been created around the Thames tributary River Lea with waterways dredged, proper transport links built and three networks of high-speed cable laid.

The ODA has also been praised for having set new and ambitious environmental and energy standards for the construction industry in London. As a result, each Olympic venue might be at least 15 percent more energy efficient than existing requirements, with the Velodrome double that level, according to officials. On a whole, the Olympic park is likely to become 50 per cent more carbon efficient than would be required by British regulatory standards.

However, the park redevelopment has been criticised by environmentalists for its lack of renewables. The pledge to supply 20 per cent of power from renewable sources fell short, after planning and technical complications meant abandoning a wind turbine plan, with renewables now likely to produce only 10 per cent of the energy needed. In autumn 2010, the London Assembly’s environment committee also warned that the London 2012 Games might not be as transformative as predicted. It pointed at the organiser’s failure to secure electric cars and to come up with a plan to offset emissions for travel to the Games next year, adding that the capital’s poor air quality had not improved much as a result.

Despite the criticisms, the overarching promise to transform a former urban wasteland into what will soon be a decent neighbourhood for leisure and living is on track. In terms of wildlife, the Olympic park will incorporate an area of about 45 hectares as protected habitat for hundreds of existing and rare species, from kingfishers to otters, and with a total of 525 bird boxes, and 150 bat boxes installed. With more than 4,000 trees and 300,000 wetland plants planted, the park will also exemplify the UK’s largest ever urban river restoration project.

Venue legacy and re-use

Venue legacy and re-use

To make sure that east Londoners are left with a substantial post-Games legacy, the Olympic Park Legacy Company (OPLC) is in charge of seeking operators for all aspects of the Olympic Park. The park will not only house the Olympic stadium and the press and broadcast centres, but also the swimming, cycling, handball and basketball facilities.

Trying to save money, the remaining sports will take place either in newly built but temporary facilities or they will re-use already existing arenas in other parts of the cities, such as the Greenwich Park for equestrian sports or Wembley Stadium for soccer. If anything, the use of existing facilities has allowed London to focus on the post-Games future and legacy for the buildings, trying to avoid ‘white elephants’ (the British expression for redundant facilities or objects) as has been the case in the past Summer Olympics, often leaving host cities with under-utilised facilities and tax payers frustrated for years.

While the OPLC has not yet achieved its goal, such as with finding a tenant for the Olympic park’s media centre, some achievements have been made. A year to go before the start of the Games, a new anchor tenant for the £537m Olympia stadium has been found. London received competitive offers for the 80,000-seater from Premier League soccer team Tottenham Hotspur, but ultimately awarded it to soccer club West Ham United together with Newham Council, who promised to retain the running track allowing the stadium to also host track and field events in the future.

Tottenham appealed against the decision taken by OPLC because the West Ham bid included a £40m loan of public money from Newham borough council, which accordingly distorted the bidding process. The issue is likely to rumble on, back and forth, until the games are long over. Before being handed over to its new proprietor, the stadium’s 55,000-seat upper tier will be stripped out after the Games, with materials recycled or re-used, decreasing its capacity to merely 25,000 seats thanks to its flexible design.

The Olympics Aquatic Centre will be transformed into a community swimming pool for professionals as well as local schools and clubs, while the basketball arena will be dismantled and is being considered for reuse during the Chelsea Flower Show or the Glasgow Commonwealth Games in 2014. A particular site of pride for the Olympic organisers is the athletes’ village’s-come-tenements with its 2,800 state-of-the art apartments, featuring smart energy metering and high-speed cable. Once the Games finish in September 2012, one half will be converted into private estate and the other into government-funded council housing re-opening in summer 2013. In addition, new education facilities, health centres and a retail park are planned to open nearby.

If anything, the Olympics are a real boon for the East End’s deficient public transport network. At the nearby Stratford International train station, thanks to the Olympics a new high-speed rail link will eventually offer new connections to continental Europe. In addition, a new train service will connect the Olympic Park with St. Pancras station, while the Jubilee tube line, the Docklands Light Railway and bus services have already been extended, offering local residents better public transport into the rest of the city.

In line with mayor Boris Johnson’s key political achievement of his first term in office, the city-wide roll-out of a public bicycle hire scheme, the hiring scheme is also planned to be installed in the park whilst at the same time restricting car access and parking space.

Community engagement, tickets and safety

As with every Olympics, local residents fear that they end up having to bear with the negative consequences of a mega-event so close nearby, such as rising rents, forced resettlements and a general hike in living costs and council taxes. In addition, local groups have protested the disappearance of green spaces, such as Hackney Marshes and Wanstead Flats.

Expressed by UK consumer groups, discontent also mounted over the mechanism adopted by LOCOG to allocate the 8.8m Olympic tickets. After two rounds of public ballot, only 850,000 individual applicants have been successful in securing more than 3.5m tickets, about 40 per cent of the total tickets, leaving still millions of sports fans and Londoners without any. While the goal is to get as many members of the British public to the Games as possible, it might end up as a disappointing experience for the majority.

With the eyes of the world having turned to London already, the runaway riots that took place in early August 2011 could not have come at a worse time for the capital. The riots initially broke out in the district of Tottenham, when a demonstration against the death of a local resident by police turned violent and cars and shops were set ablaze. Bursting upon a leader-less and largely overwhelmed Metropolitan Police force and spreading over to other parts of London and other English cities in no time, worries about scenes of civil disturbance during the time of the Olympic Games have been expressed in news reports all over the world accompanied with pictures of burning buildings and cars.

That much of the pre-Olympics goodwill has dissipated at the hands of the rioters suggests a recent poll commissioned by the London Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Carried out among more than 130 London businesses, the overwhelming majority (83%) believes that the riots have damaged the capital’s reputation as a place to do business, and nearly three out of four businesses agree that the riots have highlighted the potential threat of civil disorder during the Olympic Games next year.

But it's not just about safety. With the riots in mind, convincing poorer parts of London that the Olympics will improve local people’s lives isn't getting any easier. Still, the International Inspiration Programme announced just weeks before the riots that it had realised its targets a full year before the opening ceremony to reach 12 million young people around the world and connect them to the power of the Games by inspiring them to do sports.

Now the question looms whether London's own youth was addressed sufficiently enough? Or how the organisers could have embedded the legacy effects better in the communities of London and in particular of the East End itself, of which many were most affected by the riots?

Fears and hopes

It never has been an easy undertaking using a temporary event, such as the Olympic Games, to create a lasting legacy. Too many conflicting interest and too many unrealisable desires and expectations are raised - perhaps inherent in large urban redevelopment schemes of all kinds - that make it virtually impossible to satisfy everyone.

So far, London has been doing an excellent job in its preparations, much better than many other host cities in the past, and is well on track to achieve its set-out goals. At worst, the Games could be undermined by similar scenes of rioting or protests during next summer, leaving audiences around the world in discomfort. At best, it could set a lasting example of truly integrated urban planning and could become a role model for the upcoming host cities (Sochi in 2014; Rio de Janeiro in 2016) in terms of legacy and as a benchmark for environmental sustainability, just like Barcelona or Sydney became in time.

Comment on this article

Read comments