Typical London Tube train leaving station

FRONT PAGE

Site Search

About us

Barcelona Metro

Berlin U-Bahn

Guangzhou Metro

Guatemala City TransMetro

London Transport

London Underground

Madrid Metro

Mexico City Metrobus

New York City Subway

Paris Métro

Sao Paulo Metro

Seoul Metro

Singapore Metro

Tokyo Metro

Britain's community railways

Bus Rapid Transport Latin America

Bus Rapid Transport India

Trams in Europe

Worldwide | Elections | North America | Latin America | Europe | Asia | Africa |

|

|

London Underground carries

three million people every day

By Andrew Stevens

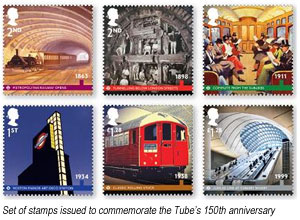

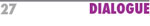

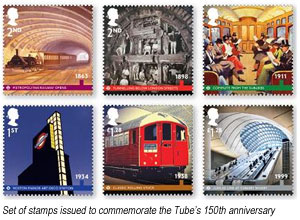

14 January 2013: Heritage and modernisation are the watchwords for London’s underground rail network, the ‘tube’, as it reaches its 150th anniversary. The world’s first underground railway, between Paddington and Farringdon Street was opened by the Metropolitan Railway in December 1863. Today, London Underground carries three million passengers a day across 275 stations on its 253 mile network.

• History

• Design & layout

• User experience

• Ownership

• Future expansion

• National comparisons

History History

The world's first underground railway, between Paddington (Bishop's Road) and Farringdon Street was opened by the Metropolitan Railway on 10th January 1863. The initial section was six km (nearly four miles) in length, and with trains hauled by steam engines provided both a new commuter rail service and an onward rail link for passengers arriving at Paddington, Euston and King's Cross main line stations to the City of London.

By the end of 1868 another company, the Metropolitan District, had opened a line between Westminster and South Kensington, where it linked up with a branch line built by the Metropolitan Railway from Edgware Road. Extensions eastwards by both the District and the Metropolitan enabled the Circle Line of today to be completed by 1884. All these lines were built by the cut and cove method, which involved excavating a trench - usually in the middle of a roadway - then covering the tracks with a brick-lined tunnel and finally restoring the surface.

By the end of the 19th century, the cut and cover system had been abandoned in central London because of the disruption and traffic congestion it caused during construction. But in the suburbs and further afield, the Metropolitan Railway had been extended by 1900 out across Middlesex and through Hertfordshire into Buckinghamshire to Aylesbury.

The oldest section of today's Underground in fact predates the Metropolitan Railway by 20 years. The Thames Tunnel between Rotherhithe and Wapping, the first such structure under water anywhere in the world, was built by Sir Marc Brunel and his famous son, Isambard. The method they adopted was similar to coal mining, sinking vertical shafts and then excavating the tunnels from within a metal shield. It is a tribute to the Brunels that major refurbishment to the tunnel fabric was only needed during 1990s. Although it was designed for horse-drawn traffic, it opened in 1843 for pedestrians only, became a railway tunnel in 1869 and now carries the East London Line under the Thames. In 1870, another railway under the Thames opened with a cable-hauled line between the Tower of London and Bermondsey. That venture was no more successful in its original guise than the Thames Tunnel, and was converted for pedestrian use after just a few months (and closed altogether when Tower Bridge opened in 1894).

Once the cut and cover system of construction had been abandoned, new lines from the 1880s in central London and the inner suburbs have been built in twin tunnels some 20 metres underground, where a layer of clay made excavation relatively simple. The first such line was the City and South London Railway, which ran for 5.2 km (3.25 miles) from King William Street in the City under the Thames to Stockwell. This was planned as a cable-hauled railway, but it opened in1890 as the world's first deep-level electric railway. This and subsequent similar lines have since always been known as tube railways.

The Waterloo & City Railway, also passing under the River, opened in 1898, followed two years later by the Central London Railway, known as the “Two-penny Tube", from Shepherd's Bush to the Bank. Its popular name came from its fare of 2d (just under 1p) for any length of journey. Early this century, three American-financed tubes were built. The Baker Street & Waterloo Railway (soon abbreviated to “Bakerloo") opened in 1906; the Great Northern, Piccadilly & Brompton Railway (also opened in 1906, and now part of the Piccadilly line); and the Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead Railway (opened in 1907, and now part of the Northern line).

The Underground expanded rapidly between the wars, reaching Ealing Broadway in 1920, Edgware in 1924 and Morden in 1926. 1932 and 1933 saw the Piccadilly extended to Uxbridge and Cockfosters, and the District to Upminster. The Metropolitan reached Watford in 1925 and Stanmore in 1932.

A single authority, never officially but always popularly known as London Transport, was set up in 1933 and immediately began formulating plans to expand the Underground further both by building new extensions and by incorporating existing suburban lines. However the 1939-1945 war intervened, and eight km (five miles) of tunnel on the uncompleted eastern extension of the Central line even became an underground aircraft component factory.

Many tube stations were used as shelters during bombing raids. After the war, the Central line scheme was completed, with the new tunnels to Newbury Park opening in 1947, and the extensions to West Ruislip and Epping opening in 1948 and 1949 respectively.

The first new tube line in central London since 1907, the Victoria Line, was opened in 1969, with the southern extension to Brixton following in 1971. In December 1977 an extension of the Piccadilly line beyond Hounslow West to Heathrow Airport was opened, and a further single-track loop to serve the airport's new Terminal 4 opened in 1986. The Jubilee line was opened in 1979.Work started on the £3.5 billion extended Jubilee line in December 1993. Designed to carry up to 30 000 people per hour in each direction, the 16 km (ten mile) line runs from Green Park to Stratford via Westminster, Waterloo, Southwark, London Bridge, Bermondsey, Canada Water, Canary Wharf, North Greenwich, Canning Town and West Ham. The extension was completed in 1999.

Design and layout

There are two distinct types of train, known as surface and tube. The term surface applies to the trains on the Metropolitan, District, Circle, Hammersmith & City, and East London Lines, the oldest parts of the Underground system. In central London, they run through cut and cover double tunnels just below ground level, and are larger than the trains, which run on the deep-level tube lines (Bakerloo, Central, Jubilee, Northern, Piccadilly, Victoria and Waterloo & City).

Steam locomotives fitted with special equipment hauled the earliest surface trains, which condensed much of the spent steam back into water. Electric trains first appeared on surface lines in the early 1900s. Steam locomotive-hauled trains were obviously out of the question on the deep-level tube lines and electric locomotives hauled the early trains on these lines. In 1903 the Central purchased motor cars, which had a driving cab and a compartment behind the cab housing the motors. This design became standard on tube lines for the next 35 years, but from 1936 London Transport introduced trains with the motors and other electrical equipment below the floor, thereby increasing seating capacity. Trains built between 1959 and 1964 for the Central and Piccadilly Lines had unpainted aluminium bodies, and those built in 1967 for the new Victoria line were also equipped for automatic operation.

On the earliest tube trains, passenger entry and exit was by way of mesh gates at the end of each car. The gates were opened and closed by gatemen. Air-operated doors, usually under the control of a guard, were introduced on tube trains from 1920. Steam-hauled trains on the surface lines originally had compartments, but when electric trains were introduced early this century access was passenger-operated sliding doors rather than gates, and by air-operated doors from the mid-1930s. The latest surface and tube cars have passenger-operated doors with push-button control, ensuring that on open-air sections of the Underground (over half the system, despite its name) only those doors though which passengers wish to alight or board are opened, conserving train heating in cold weather.

In the first significant use of the Private Finance Initiative (PFI) for funding major public transport projects, Alstom has provided 106 new trains for the Northern Line. The first of the new trains came into service in 1998, replacing some of the oldest trains on the system. Alstom have also built the new trains on the Jubilee line.

The trains on other lines (the Circle, Victoria, Bakerloo, Piccadilly and Metropolitan lines) have recently been, or are being, refurbished, including the introduction of the corporate red, white and blue livery in part to overcome the effects of graffiti. Plans are also being developed to modernise District line trains.

User experience

As the world’s oldest subway system, the London Underground is a system of contrasts. For the enthusiast, there are a number of different styles of train and station architecture, from the ornate art deco of the Piccadilly Line to the ultra-modern grey tones of the Jubilee Line extension.

In terms of cleanliness, the tube has improved vastly in recent years and a journey is rarely likely to be spoiled because of this. Station staff are vigilant over any issue that can arise and minimum standards are agreed between London Underground and private contractors. Some visitors may regard some stations as shabby but a multi-million pound modernisation programme is underway that hopes to renovate the network fully while retaining the character of its oldest stations, which are architectural gems in their own right.

Where the network falls down is on three main points. Firstly, coverage. While West London is amply covered by the network, there are parts of East and South London that remain uncatered for due to historic reasons. Several decades of under-investment have exacerbated this further. Secondly, there is the issue of the tube’s operating hours. As the network requires nightly maintenance and cleaning, the tube tends to shut down around 12.30 on most nights. Many Londoners find this inconvenient, as do tourists. And finally, the recent investment in the tube has seen an increase in the amount of maintenance work being undertaken, which means that key lines are sometimes closed to allow for this.

The tube also compares badly to other metro systems elsewhere in the world on price but for the regular user, the new Oyster card system allows for unparalleled integration with other public transport in the capital.

Ownership

London Underground Ltd is a company under the control of a public authority, Transport for London (TfL). TfL was set up as a functional body of the Greater London Authority (GLA) in 2000, with a board appointed by the Mayor of London. However, responsibility for the Underground was not transferred to TfL until 2003. This was to enable the Public Private Partnership deal to go ahead, in spite of the Mayor of London’s opposition.

Prior to the establishment of the Greater London Authority, London Underground has largely existed in the public sector but under central government control. In 1933, the London Passenger Transport Board was created to oversee all public transport in the capital and in 1948 this was officially nationalised as the London Transport Executive, a division of the British Transport Commission which also controlled airports, docks, railways and road freight. In 1963, this then became the London Transport Board, which reported directly to the then Ministry of Transport. This then became the London Transport Executive in 1970, which was passed to the then Greater London Council. Yet in 1984, relations were once again centralised when London Regional Transport was created under the control of the Department of Transport.

Future expansion

Though not running along tube lines, the London Crossrail project is one of the largest expansions of the capital's public transport network in years. Ostensibly it will connect both mainline and tube stations in East and West London, with a single line running through central London between Paddington and Liverpool Street. However, the project has suffered immeasurably from stop-start construction and financial pressures. Similarly, the East London Line extensions to connect Hackney in the North with Croydon in the South, while bringing the tube network to neglected areas of London, also suffered from delays due to financial considerations. The new privately-operated line (now part of London Overground) opened in 2010.

In 2004, the Mayor of London published his 2016 masterplan, which outlined how he would like to see the tube network expand by 2016. In addition to Crossrail and the East London Line extension, the planned light rail schemes in West London and Greenwich were also mentioned. However, this was largely a PR exercise to try and lever extra funds for London transport from central government and has no binding effect on the policies of either the government or the GLA. Recent discussions around expanding the Docklands Light Rail network have even suggested a spur into central London to relieve capacity on the tube, although these plans remain very distant and subject to cancellation.

National comparisons

Of Britain’s two subway systems proper, the other seven metro systems being light rail, London’s is by far the largest and most extensive, although Glasgow’s is still the world’s third oldest (built 1896). The London Underground also connects to two of the light rail schemes, the Docklands Light Railway and the Croydon Tramlink.

The author would like to thank the staff of the London Transport Museum for their assistance in the preparation of this article.

|

|

|

History

History