The London Underground roundel was first introduce on station platforms in 1908

FRONT PAGE

Site Search

About us

City brand Amsterdam

City brand Brasilia

City brand Bucharest

City brand Chicago

City brand Hong Kong

City brand Jakarta

City brand London

City brand Singapore

City brand Tokyo

US mayors on Twitter

Europe's top city brands

EUROCITIES branding report - a critical review

EUROCITIES on city branding

Cities into successful brand

Social media and government

Top level city domain names

Gallup's Soul of the City

Mayor of London

London City Hall

Worldwide | Elections | North America | Latin America | Europe | Asia | Africa |

|

|

The London brand:

2000 years young

By Andrew Stevens

20 October 2012: London may have long survived on Dr Johnson’s well-worn dictum that “there is all in London that life can afford” but it was iconography, which established it as the world city during the 20th century. As a nexus for world trade at the peak of the British Empire, the city remains pre-eminent as global hub in the 21st century, the ‘capital of capitals’, despite the occasional wobble and dented prominence following its de-industrialization and struggle to find its place in the world. In 2012 it benefited from considerable exposure via the London Olympics and Paralympics and continues to market itself on the back of staging the games as the world’s next big tech centre.

• History

• Brand partners and stakeholders

• Campaigns

In the first decade of the new century, the story of the London brand has been to find its purpose and re-assert its presence among the emerging global cities of the urban century. Ahead of 2012 it had hoped the eyes of the world would be upon it for the Olympic Games, but the 2011 summer riots in the capital may have temporarily shaken confidence in its ability to deliver secure games. In the event, despite the odd characteristic wobble, since laughed off by the London Mayor, all proceeded to the host city’s credit.

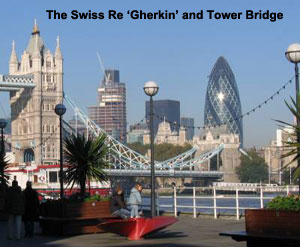

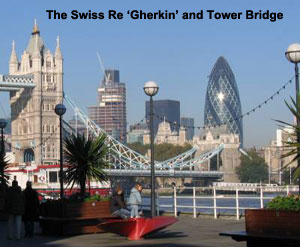

History History

The British capital can point to an array of globally recognized landmarks, from the tower of Big Ben and the neon facade of Piccadilly Circus, as well as the well-embedded consciousness of the ‘London calling’ radio signature of the mid-20th century, through to the millennial London Eye, ‘Gherkin’ tower and the recently completed Shard tower. And yet it almost seemed at one point that the fate to befall London wasn’t so much its eclipse at the hands of longstanding rivals Paris and New York or the newly emerging centres of Asia, but the likes of Frankfurt and Amsterdam.

To understand the position in which London found itself in at the beginning of the 21st century requires a quick recap of the chronic under-investment in the capital’s resource base (despite the ‘big bang’ of the mid-80s which propelled the ailing City of London into pre-eminence among finance centres) and devaluation of its city leadership through the abolition of its own metropolitan institutions during a typical spat between the UK government and a more radical city figurehead under the leftist Ken Livingstone, which left the capital with no city-wide government or representation for 14 years. Even the economic adviser to the current Conservative mayor Boris Johnson admits that these were dark days for the capital and only now does London believe in itself again. For all intents and purposes, from the tawdry strip-show alleys behind the neon of Piccadilly’s cinema-friendly facade to what Ed Glaeser has in The Triumph of the City dismissed London’s restaurant offer of the era as being of ‘the Scotch egg’, the capital exhibited all the signs of expiry at the behest of its reduced circumstances.

And yet recovery arrived, though perhaps the tide of optimism which restored city-wide government in 2000 was shared equally with the election of a Labour government under the youthful Tony Blair, marketed as ‘Cool Britannia’ as part of the Foreign Office’s attempts to re-engineer British public diplomacy for the new millennium. The starting gun for this was fired by a 1996 Vanity Fair cover story of ‘London Swings Again’, though as its author acknowledged a decade on, by the early 2000s the cover stars were divorced, the cultural elite washed out and the UK brand tainted by an unpopular war in Iraq.

But London’s brand was formally recognized by the city authorities (after years of being subsumed into national trade and investment promotion), not least as Ken Livingstone’s two terms as London mayor were defined by himself and his advisers as being a project to reposition and indeed reshape London as a ‘city state’ based on the finance-led economy of the City and the vibrant social liberalism of its diverse population. The second mayor, Boris Johnson, has largely concerned himself with the public realm, such as banning alcohol from public transport, introducing the so-called ‘Borisbike’ cycle hire scheme and new generation London Buses and aiming for a more ‘village’ feel in parts of the capital.

This latter period also saw the capital’s resolutely low-rise skyline altered with the addition of several new tall buildings in the City to augment Big Ben further down the Thames. The familiar and popular black cabs and red phone boxes of London can sometimes act as a double-edged sword, either underscoring external perceptions of a congested, run-down city or skewing brand alignment among domestic audiences in the UK, where the capital is seen as affluent but arrogant and somewhat staid and lacking in originality to the point of cliché.

Within Europe, London suffers from a poor perception of costs associated with both visiting and living in the capital, from tourist prices in the centre to the cost of renting and commuting. The roundel of London Transport is an instantly recognized global symbol for the capital, the closest it comes to a logo (another is the font of the City of Westminster’s street signs, Abbey Road and so on). And yet while it remains a truism in most countries that the capital is not interchangeable with the country as a whole, most UK branding has concentrated on London’s offer, while the country itself remains heavily centralized and dependent on its capital. This conundrum can be seen either way as investment in and stewardship of the capital brand or just the typical swagger and braggadocio the rest of the UK associates with London.

The summer 2011 disturbances which raged across several nights in districts of the capital undoubtedly dented the city’s image globally and not only confirmed a return to the recessionary dark days, but also raised doubts about the safety of the 2012 Olympics. While the riots were for the most part concentrated in urban centres on the periphery, even the Hugh Grant fairytale romance of Notting Hill was shattered by diners robbed at knife-point in an upscale restaurant (saved only by foreign chefs, testament to the worth of London’s diverse population). The city authorities, who control both external promotion and policing, maintained it wasn't possible to quantify to what extent London’s tourism and investment profile was actually damaged by the scenes broadcast of mob rule in retail parks and burning high streets, but equally subsequent foreign coverage focused on the resilience of Londoners and their communal solidarity in facing down the rioters and coming together to clean up and bounce back in the days that followed.

The autumn's 'Occupy' protests outside of St Paul's Cathedral shone something of a spotlight on the antiquated workings of the City of London Corporation which was the target of the protestors' ire, further underlining external perceptions of not a welcoming 'world's metropolis', but a city characterized by the gulf between the haves and have-nots. However, the conundrum to be faced down in the eyes of the city authorities is that of political and media 'banker-bashing' warding off future investors or forcing existing ones to consider relocation elsewhere.

Brand partners and stakeholders Brand partners and stakeholders

Since April 2011, responsibility for promoting the capital has rested with the London & Partners agency, which is a non-profit organization funded by the Mayor of London with an annual grant. The agency was established to bring together the former promotion bodies for the capital – Visit London (tourism), Think London (investment) and Study London (universities) – following a reduction in central government funding for economic development, which led to the abolition of the London Development Agency (LDA, which funded the three bodies). The agency oversees all external promotion campaigns for the capital, domestically and internationally, working with the private sector, who are represented on its board. In 2009 the Promote London Council was established by the Mayor to advise on the roll-out of a unified brand for London ahead of 2012, bringing together stakeholders from public and private sectors. The voice of business is represented through London First, which became the capital’s first investment agency in 1994.

In addition to the work undertaken across the capital by the Mayor of London, the City of London Corporation, the historic ‘square mile’ at the centre, undertakes its own work to promote the City of London internationally as a brand for the financial district. This work is spearheaded by the Lord Mayor of the City of London, who acts as Ambassador for the City and the financial services industry on global tours each year. The Lord Mayor, not to be confused with the elected Mayor of London Boris Johnson, is an honorary post appointed each year by the Corporation in a practice which dates back to 1189. The City is also represented on the Promote London Council.

Given the centrality of the West End to London’s retail and leisure offer, the New West End Company (a Business Improvement District) is responsible for marketing the shopping quarter around London’s Oxford and Regent Streets. In recent years and despite the recession, the West End has become a designated luxury shopping experience (such as Bond Street and the Burlington Arcade) and efforts are being made to target the emerging Chinese middle class as well as more traditional high end markets in the Middle East, Europe and the US. In August 2011, just days after the riots, it signed a retail twinning partnership with Tokyo’s upscale Marunouchi district aimed at increasing Japanese tourist spend. The New West End Company also shares its chairman, Dame Judith Mayhew Jonas (a former leader of the City of London), with London & Partners.

The East London Tech City project was launched in late 2010 by Prime Minister David Cameron following the clustering of emerging internet firms around the Old Street roundabout, later dubbed ‘Silicon Roundabout’. Envisaged as a technology hub with growth potential stretching from the boundaries of the City to Hackney’s media facility for the 2012 Olympics, it enjoys the support of the London Mayor, UK Trade and Investment and a range of private sector and academic sponsors, although the main drivers are the firms themselves and incubator facilities. Post-games, Tech City (as it is now known) has emerged as the main pillar of the UK’s overseas promotion strategy, aligned to the ‘technology’ strand of the government’s GREAT campaign.

Where London branding lacks cohesion is the 32 London Boroughs, the bulk of which give the capital its population quota to assert itself as a megacity but in themselves act solely as service delivery units, the outer periphery of which suffer from under-investment and a lack of sense of place (kebab shop-lined high streets, for the main part) as shown recently by the week of disturbances which barely had any effect on London’s central Zone 1.

Ostensibly the legacy of the interregnum when the capital enjoyed no city-wide government and also the willful denial of local identity by central government in the 1960s when such anodyne names as Brent and Waltham Forest were bestowed upon them, the lack of worked out place branding by the boroughs has led to the pervasive sense among visitors and residents alike that such localities lack any meaningful identity or sense of place other than to act as dormitory zones to feed into the vibrant centre.

Campaigns

In the first part of the last decade, London grappled with an array of competing subsidiary brands, for instance the ‘Totally London’ campaign, which sat atop marketing efforts for the West End, among others. Both the Mayor’s office and the New West End Company now ensure that campaigns compliment rather than compete and sit within an organized hierarchy. The first conscious effort to unify the brands began in 2006 with the London Unlimited project of the LDA, which brought in private sector expertise to leverage the city’s efforts in a more cohesive and commercially-friendly manner, particularly in the run up to 2012.

The process was then revised into the Promote London Council and its steering of the three agencies, now London & Partners, which work according to the ‘Only in London’ campaign which seeks to stress the capital’s unique tourist offer. The overall aim however was for a so-called ‘halo effect’, starting with the Royal Wedding in 2011 and leading into both the Olympic Games and the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012. In the event, post-games tourism figures showed a slight decrease in visitor numbers compared to the previous summer.

A series of one-off events was mounted in the run up to the games as ‘Limited Edition London’, in order to capture attention outside of the event, especially among those likely to be deterred by or disinterested in the games. However, while the organizers of the 2016 Rio games are wholly conscious of the need to deliver a secure games for the world in an often dangerous city, London’s were probably not expecting to have to counter the negative press of August 2011 and the doubts surrounding the over-stretched police’s ability to cope.

All agencies under the Mayor’s direction work according to the goal of making London “globally recognized as the best big city on earth”. In January 2010 the Mayor agreed to work towards a unified brand for London and appointed Saffron Brand Consultants to oversee the work, directed by a London Brand Steering Group chaired by his then director of marketing (Dan Ritterband, formerly of Saatchi & Saatchi). In March 2011 however it was announced that all branding work would be subsumed into London & Partners and that a unified brand would not be rolled out across London’s public bodies but would instead build on the existing ‘Visit London’ logo with the addition of 12 brand ambassadors from the creative industries as ‘London: Human Capital’. Following the Olympics, the mayor’s director of communications Will Walden assumed responsibility for London’s marketing strategy.

|

|

|