Carlos Ocariz, Mayor of Sucre, Miranda, Venezuela

FRONT PAGE

About us

MAYORS OF THE MONTH

In 2015

Mayor of Seoul, South Korea (04/2015)

Mayor of Rotterdam, Netherlands (03/2015)

Mayor of Houston, USA, (02/2015)

Mayor of Pristina, Kosovo (01/2015)

In 2014

Mayor of Warsaw, Poland, (12/2014)

Governor of Tokyo, Japan, (11/2014)

Mayor of Wellington, New Zealand (10/2014)

Mayor of Sucre, Miranda, Venezuela (09/2014)

Mayor of Vienna, Austria (08/2014)

Mayor of Lampedusa, Italy (07/2014)

Mayor of Ghent, Belgium (06/2014)

Mayor of Montería, Colombia (05/2014)

Mayor of Liverpool, UK (04/2014)

Mayor of Pittsford Village, NY, USA (03/2014)

Mayor of Surabaya, Indonesia (02/2014)

Mayor of Santiago, Chile (01/2014)

In 2013

Mayor of Soda, India (12/2013)

Mayor of Zaragoza, Spain (11/2013)

Mayor of Marseille, France (10/2013)

Mayor of Schwäbisch Gmünd, Germany (09/2013)

Mayor of Detroit, USA (08/2013)

Mayor of Moore, USA (07/2013)

Mayor of Mexico City, Mexico (06/2013)

Mayor of Cape Town, South Africa (05/2013)

Mayor of Lima, Peru (04/2013)

Mayor of Salerno, Italy (03/2013)

Governor of Jakarta, Indonesia (02/2013)

Mayor of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (01/2013)

In 2012

Mayor of Izmir, Turkey (12/2012)

Mayor of San Antonio, USA (11/2012)

Mayor of Thessaloniki, Greece (10/2012)

Mayor of London, UK (09/2012)

Mayor of New York, USA (08/2012)

Mayor of Bilbao, Spain (07/2012)

Mayor of Bogotá, Columbia (06/2012)

Mayor of Perth, Australia (05/2012)

Mayor of Mazatlán, Mexico (04/2012)

Mayor of Tel Aviv, Israel (03/2012)

Mayor of Surrey, Canada (02/2012)

Mayor of Osaka, Japan (01/2012)

In 2011

Mayor of Ljubljana, Slovenia (12/2011)

Worldwide | Elections | North America | Latin America | Europe | Asia | Africa |

|

|

Mayor of the Month for September 2014

Carlos Ocariz

Mayor of Sucre, Miranda, Venezuela

Interview by Tann vom Hove

5 September 2014: Since Venezuela’s late President Hugo Chávez organised a referendum in 2009 to allow him to remove a presidential two-term limit from the constitution, the country has been regarded as a one-party state run by the United Socialist Party (PSUV). But while the ruling party dominates national politics through its strong majority in the National Assembly and the country’s powerful President, opposition parties govern in some important states and Venezuela’s largest cities, including Caracas.

• Opposition mayors

• Mayor Carlos Ocariz

• Interview with Mayor Ocariz

Opposition mayors

In last year’s municipal elections, an alliance of opposition parties gained more than 39 per cent of the vote, while, with a result of 49 per cent, the ruling socialist coalition failed for the first time since 2007 to gather a majority of votes in country-wide elections. The opposition Democratic Unity Alliance (MUD) now controls six of the ten largest cities and nine of the 23 state capitals.

Opposition mayors have been a thorn in the side of Venezuela’s left-wing government since 2008 when Leopoldo López, the popular Mayor of Chacao, announced his candidacy for the mayoralty of Caracas, which was then still held by the ruling socialists. The government’s response was to ban him and 371 other local candidates from standing in elections. López and two other former opposition mayors are currently on trial on charges of supporting anti-government protests earlier this year.

Despite trying to stifle opposition politicians, 2008 was not a good year for Hugo Chávez’s government. Crude threats by the President - he said he might have to bring out the tanks if the opposition won in some crucial states and cities - the government lost control of the country’s capital Caracas and of the three most populous states, Zulia, Miranda and Carabobo.

Mayor Carlos Ocariz Mayor Carlos Ocariz

The most painful result for Venezuela’s ruling party in 2008 was the loss of Sucre, one of the five municipalities that make up metropolitan Caracas. Contested by a confidant of President Chávez and depicted by a writer of the Chavismo movement as a place where a loss could threaten the Bolivarian revolution in Latin America, the city was won by Carlos Ocariz from the centre-right Justice First party. The London-based Economist magazine described his victory in the sprawling slums of eastern Caracas as particular painful for a government that claimed to be fighting a class war on behalf of the poor. “By favouring Ocariz, urban voters showed that they were worried by the rampant crime, inflation and poor administration that are starting to eclipse generous oil-financed social programmes as the hallmarks of Mr Chávez's rule.”

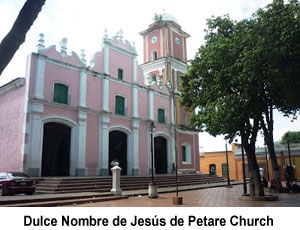

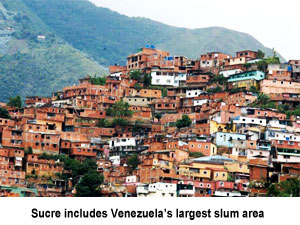

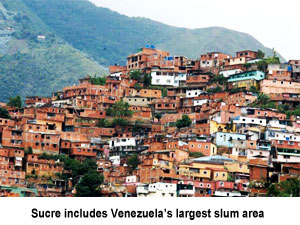

In a recent essay, Daniel Lansberg-Rodriguez, who served in Mayor Ocariz’s first administration, depicted the situation inherited from the previous regime as unworkable chaos. “We brought some semblance of order but only by thinking, and eventually reaching, far outside of the political box,” he wrote and also compared Sucre with New York’s Bronx. “Sucre has scattered pockets of wealth and a few local industries but is almost entirely eclipsed by Petare, Venezuela’s largest slum.”

The election of Carlos Ocariz provided the opposition with a much-needed boost, but Lansberg-Rodriguez admitted that the success stemmed, in part, from outside factors: “The two-term previous mayor of Sucre was at that time José Vicente Rangel Ávalos, the millionaire son of an eponymous, famous and ancient Venezuelan communist turned celebrated Chávez ally. This socialist scion, whose nepotistic rise would saddle him with the unshakable nickname ‘Papi Papi,’ seemed to spend much of his eight-year mayoral tenure focused more on interparty politics and high-profile business ventures than on public administration.”

Since first elected Mayor of Sucre in 2008 and re-elected in 2013, Carlos Ocariz has become one Venezuela’s best-known opposition politicians. Prior to entering politics, Ocariz, who has a degree in civil engineering, served for three years (1996 to 1999) as an adviser on social and health issues to the Governor of the State of Miranda. At only 24 years old, while working for the Miranda state government, Ocariz founded the State of Miranda Social Development Foundation, through which he and other professionals sought to attain greater citizen participation over budget decisions and investments made in their neighborhood. The Mayor claims that through his work with the Foundation and the Miranda governor’s office, he was able to learn firsthand the struggles and needs of Sucre residents.

In 1999 he was appointed to the board of the state health authority and one year later he won a seat in Venezuela’s National Assembly, representing the Sucre municipality. Aged 29, he was the youngest member of the Venezuelan parliament.

In 2000 and again in 2004, Carlos Ocariz run unsuccessfully for Mayor of Sucre. But in 2008, after having been selected as the joint opposition candidate, he defeated the government contender by winning more than 55 per cent of the vote. During his first term in office, he made public safety, education, municipal services, transport and budgetary responsibility his priorities. His vision for Sucre was to make the city more efficient, egalitarian and secure, with opportunities for everyone. Reviewing his first years in office, Mayor Ocariz said that he had fulfilled 53 of the 60 promises he made at the beginning of his first term.

In an interview with the City Mayors Foundation, Mayor Ocariz explains how his first-term goals were met, his priorities for the next four years and how, despite political differences, his administration and the government work together.

Interview with Carlos Ocariz, Mayor of Sucre Interview with Carlos Ocariz, Mayor of Sucre

City Mayors: In 2008, your defeat of the candidate from the late President Hugo Chávez’s United Socialist Party in the predominantly working class municipality of Sucre against caught political commentators in Venezuela and abroad by surprise. What were the reasons for your victory over one of Chávez’s allies?

Mayor Ocariz: At the outset, let me provide a brief background on Sucre. Sucre is one of the region’s most populous municipalities, with over one million residents, including the most populous “barrio” in Latin America, located in the area known as Petare. The geographical and political importance of Sucre makes any election one of national interest. The municipality is located in the capital city of Caracas, and is part of Venezuela’s Miranda state, composed of a mix of middle class and lower income neighborhoods. Seventy-five percent of our city’s residents live in popular sectors, where Hugo Chávez captured a hope that would quickly become a political capital. The slow but systematic fading illusion that began with our victory has already become a clear and effective popular force.

By 2008, Chávez had been in office for 10 years. He had won reelection by a landslide two years before, and had to show strength and power in local elections, especially one year after losing a referendum that would have changed the constitution and allowed any public official to be elected indefinitely. For the United Socialist Party, there was no room for mistakes. To date, Chávez had not lost any election in Sucre.

There were many reasons that contributed to our victory. I remember that one of the most prominent writers from the Chavismo movement wrote an article that roughly said, “The destiny of the Bolivarian revolution in Latin America depends on our victory in Sucre.” That kind of summarizes the significance that our municipality had back then, and has right now.

So our campaign started. Not surprisingly, the disadvantage was notorious. As we handed citizens flyers proposals about how to improve public services, personal security and roads, our opponents tried to buy votes by giving away washing machines, microwaves, refrigerators and mattresses. Though our people needed those things, they never sold their consciences. We won using the only two weapons we had: our dream of a better future, and non-stop hard work. We walked around the entire municipality, made up of 50 neighborhoods and 2100 “barrios”, which allowed us to understand the realities of our people first hand. We understood that beyond efficiency; decentralization, the active participation of residents in politics, and government transparency were key elements to improve the quality of life in Sucre.

That 2008 epic campaigned destroyed the myth that working class people were automatically chavistas. We are proud to say that in 2008, we showed that making clear proposals and having a vision for the city trumped the old political game of patronage and negative campaigning.

The reasons for our success are summarized in disciplined and consistent work. I was elected Member of the National Parliament for this town from 2000 to 2005, and always mixed the legislative work with community social work. Through hard work, we have crafted the conditions needed for depolarization, and transparent and genuine participation of the organized community.

Proof of our success are the eight elections won in the municipality since we took office (Local in 2008, constitutional reform in 2008, constitutional amendment in 2009, parliamentary in 2010, primary in 2012, presidential in 2012, regional in 2012, presidential in 2013, and municipal in 2013).

City Mayors: During your first term, crime has significantly fallen in Sucre, while it has gone up in the rest of the country. How was the reduction achieved and could any measure you took be duplicated in other cities?

Mayor Ocariz: When we arrived at City Hall in 2008, we received a very violent city. Sucre’s homicide rate at the time was 72 per 100,000 habitants, and the trend was in the rise. We knew from the very beginning that fighting violent crime had to be our first priority.

We are proud of the crime reductions we have achieved since taking office. In 5 years as mayor, homicides have decreased by 45 percent when compared with 2008 statistics. We have achieved this, despite the fact that during this same period, crime in Venezuela as a whole has increased by 20 percent. Moreover, year after year we have reduced crime rates in Sucre by an average of 10 percent. We believe this is the highest inter-annual crime reduction rate in the world.

To achieve this dramatic reduction of violent crime in our city, we first set out three clear goals and strategies.

First: we set out to revamp Sucre’s police force. We devoted a significant amount of the city’s budget to modernizing the police force equipment, technology and training. We doubled the salaries of our policemen and policewomen. We opened a new police academy as a way to train more police in a more professional way. As a result of the increase in numbers of police, we have had a more intense police patrol presence in the streets. All of our police squad cars are now equipped with GPS devices to be able to monitor the checkpoints in the city in real time. We created a plan of “Hot Spots” that involves taking the empirical evidence and conducted patrols in specific areas, chosen by the evidence analyzed. We are pioneers in the implementation of this program, using the data base of homicides instead of emergency calls. Our program has been applied with great success and is being studied by various universities including Harvard, Columbia, George Washington, Cambridge and the University of the Andes in Colombia.

At the same time, we realized that just greater police presence would not, by itself, solve the city’s crime problems. We knew that we had to create more and better public spaces, including constructing and rehabilitating sports complexes and other areas for entertainment that would give our residents, especially our youth, greater opportunities for positive leisure. We have made over 35 tennis courts with artificial turf and recovered over 200 sports facilities. We have invested the most in the poorest neighborhoods, where we now have thousands of children and young people studying and practicing sports. Sport and education are our best weapons against violence. We developed plans to improve traffic mobility, backflow, and plans for citizenship education. This, in some cases, has reduced traffic by up to 35 percent.

Third: we knew we had to integrate the community into solving these problems. In Sucre, we identified our neighbors as the key actors in conflict resolution. We have generated methodologies where communities are involved in security, allowing proposals to arise from these spaces. Examples are the partnership we had with the private security of the municipality, and the creation of community policing.

I am convinced that the actions we have taken can be replicated in other municipalities in our country and in the world, taking into account the elements mentioned, including the importance of having an appropriate number of police, of creating educational, sporting and cultural spaces for children and youth, and integrating the community in the resolution of conflicts.

City Mayors: At the time of your first election, you also promised to improve education. You were particularly concerned about the shortage of teachers, student truancy and poor school infrastructure. Has the provision of education improved since 2008, bearing in mind that the Municipality of Sucre manages less than 20 per cent of schools in the city?

Mayor Ocariz: In our country, there is a lot of social inequality. The gap between social classes is very pronounced, and in our opinion, the best way to reduce that gap is to improve public education, making it fairer and safer. In Sucre, we are convinced that a young man who studies and is able to practice sports, is someone who will stay away from the path of crime.

We work on the basis of excellence. We have made great efforts to depoliticize education, and to make sure our teachers, doctors and police are the best paid in the country. We know that to have a more just society, we must provide quality education to future generations.

All public policy should be measurable elements to assess their performance. In our town, we have reduced the dropout rate – currently at 2 percent in our local schools. We have also increased attendance and the academic performance of our students. This we have achieved through the following mechanisms.

First: Form a team of committed quality teachers. We have improved their salaries and invested in their training. We have better teachers because we generate incentives to encourage greater commitment and greater quality.

Second: Improve educational facilities. Turn municipal schools in modern spaces. We involved parents and guardians in the process of recovery and rehabilitation of schools, thus turning them into part of the solution. The family is the fundamental unit of society, so we have promoted school-community organic links, involving parents and guardians in the education of their children.

Third: Implement social programs. We designed four social plans for education, thus ensuring that our students have the tools to improve their learning. We provide snacks, we give school supplies to those without the economic means, we support mothers in need with scholarships if their children meet a high level of attendance, and offer support to children who are visually or hearing impaired to optimize their learning. To low-income youth, we offer them the opportunity to pursue university studies in private institutions. Currently, more than 840 young people have benefited by this plan.

Our goal is to continue to strengthen our youth so they have the right tools and skills to become successful future leaders of Sucre and Venezuela.

City Mayors: Sucre consists of some middle-class areas but also Petare, which includes Venezuela’s largest slum area. Do you find it difficult as a mayor to reconcile and serve the interests of both affluent and poor citizens? City Mayors: Sucre consists of some middle-class areas but also Petare, which includes Venezuela’s largest slum area. Do you find it difficult as a mayor to reconcile and serve the interests of both affluent and poor citizens?

Mayor Ocariz: Venezuela suffers from a democratic crisis. Public institutions lack autonomy, affecting the natural dynamics of the various levels of government.

In Sucre, we have developed a model that has proven we can reconcile citizens who think differently. Our secret is that we seek to permanently break the polarization and work for everyone regardless of their origin or political stripes. We seek to be righteous in the implementation of the budget so that everyone has the same opportunities.

We handle a tool called participatory budgeting, where we divide the municipality into 42 sectors and assign a budget to each sector, relative to their proportion and level of poverty. The neighbours of each of these sectors decide and run the budget, and are accountable to the state. The budget seeks to create participatory citizenship and allows for the treatment of problems to be the same in middle class and in popular sectors.

Local politics is the real type of politics, which is why we have tried to generate the appropriate channels to depolarize our society, and together find solutions to the problems of each of the areas.

City Mayors: In a recent essay, your former colleague Daniel Lansberg-Rodriguez estimated that nearly three-quarters of Sucre’s population fall into the lowest two economic classifications, the poor and the very poor. What does your administration do or can do to improve living and economic conditions in poorest areas of your city?

Mayor Ocariz: One way or another, local policies are affected by national policies. From our office, we have worked to formalize the informal, providing tools and opportunities for low-income people to improve their quality of life.

A country develops to the extent that it has strong private enterprises that generate jobs and wealth. However, there must be certain conditions, especially a climate of trust. Our country lacks the confidence to attract new investors, there are no legal institutions, and the legal rights of private property are often violated.

We formed a Triumvirate joined by the community, the municipality and private enterprise. In the latter, we believe faithfully, and generate mechanisms to strengthen it. Thus, we have promoted job fairs, creating spaces that encourage employment and formalization of merchants. To date, we have conducted 11 job fairs in Sucre where that have allowed over 45,000 people to approach, evaluate options and get jobs. Initiatives such as this one do not cost the state anything, but they serve as a bridge to help people get a job.

We are also promoting the regularization of land tenure. Most of Sucre’s residents have lived for decades in areas they do not own. We are seeking to achieve social justice by allowing people to have access to property. We estimate to be able to deliver more than 7000 titles this year.

Finally, we have improved public services at the grassroots level, building many sports, recreational spaces, increasing the quality of education and health services, in order to generate citizenship.

City Mayors: People living in slum areas like Petare rely heavily on the informal economy, including street peddling, to make ends meet. In many large Asian and South American cities stationary peddlers – or buhoneros as they are called in Venezuela – operate to their own rules, with mayors finding it difficult to control their activities. How have you dealt with the problem?

Mayor Ocariz: The situation of informal workers in Sucre and throughout Venezuela is a result of the situation facing the country as a whole. The economic crisis the country is impacting Venezuelans of all social classes forcing many of our citizens to take to the informal economy as a way to make ends meet. In Sucre, we have a particular area where the informal merchants are highly concentrated. The so called – Redoma de Petare – is a highly congested area through which a million people cross every single day. Approximately 2,000 informal merchants gather daily in that area.

To address this issue, we have been working diligently to take merchants from the informal sector into the formal economy. We have done this by organizing, learning their needs, and offering them the tools necessary to formalize their businesses, including training in entrepreneurial skills. So far 2,000 of these merchants have been given this training.

At the same time, we have created formal market areas where these informal merchants can sell their goods. We built a market that provides a safe and clean space for informal merchants to sell their goods. In this way, we have started the process of taking merchants out of the streets, thus opening spaces around the busy Redoma area. This process to help informal merchants move into the formal economy has been a difficult and complex one. But we are proud to have opened channels of dialogue and to have addressed the issue through peaceful means – something that has not been the case in previous administrations.

City Mayors: The political landscape in Venezuela has long been dominated by the ruling United Socialist Party. Have you, as an opposition mayor, established a working relationship with the government?

Mayor Ocariz: As mayor, my duty is to solve the problems of our city in every entity within the Venezuelan government, whether local, regional or national regardless of my ideological posture. That is why we have made important coordination efforts with all levels of government. In some cases, coordination has been possible. In others, it has been an uphill battle. In one particular issue where some cooperation has been possible is in the security front. Some of the successes achieved on the security front have been due to coordination with other government entities.

It has been difficult, however, because while we firmly believe in working with everyone to achieve progress regardless of political ideology, we often confront obstacles placed by the central government in coordinating actions and improve results for our citizens.

City Mayors: More than 70 percent of Venezuelan mayors belong to the ruling United Socialist Party. Only 15 out of 337 mayors are members of your own Justice First party. How well do you work together with your colleagues from the ruling party and other opposition parties?

Mayor Ocariz: In December 2013, Venezuela held municipal elections across the country. While the ruling national party won most of the mayoral races, the opposition candidates were victorious in the most important cities of the country. The population of these large cities is where most Venezuelan’s live. Therefore, we can say that across the country there is a plurality of political parties represented in local governments.

Just like we have made an effort to achieve greater coordination with the central government, we have done the same with the different city halls across the national, regardless of how they lean politically. What we have strived to do while in office, that of removing politics from the administration of the city, we have done when dealing with other mayors. Sometimes it’s complicated but we have permanently sought to lower the political divisions in the country because we firmly believe it’s the best way to achieve progress for all Venezuelans.

City Mayors: In March this year, you and other mayors founded the Association of Mayors for Venezuela. But it has only 70 members who are presumingly all members of opposition parties. Will the new Association be in any position to influence government policy?

Mayor Ocariz: The Venezuela Mayors Association was born out of a need to join efforts and fight for the democratic principles that its elected officials share and the defense of our citizens. Venezuela’s political institutions are weaker as every day passes and the central government actively seeks to concentrate more power in itself.

The association we have created is composed of 76 Venezuelan mayors, representing diverse political parties and independents. Together, we work toward protecting the independence of local governments, their autonomy and rights. In Venezuela, we experience arbitrary detentions such as the one’s suffered six months ago by two of our fellow mayors – Enzo Scarano and Daniel Ceballos. These two colleagues remain in detention as political prisoners of the government. Through these arbitrary actions, the national government aims to plant fear among those who oppose it. Mayors Scarano and Ceballos were democratically elected on December 8, and without the appropriate due process as required by law, they remain detained as political prisoners. Their judicial trial is being conducted without any semblance of transparency typically found in any democratic society.

These two mayors, however, are not the only political prisoners at the hands of our national governments. There are dozens of cases of political leaders, students, former military officials and many others who have been forced to leave the country, and who have been subjected to arbitrary detentions and threats.

The Association of Mayors has also spoken out forcefully with respect to the budget crisis faced by many cities across Venezuela. This crisis is a result of the central government’s unwillingness to disburse funds to city governments. We believe that by joining forces, we can raise awareness more effectively about these issues.

City Mayors: What are your priorities for your second term in office?

Mayor Ocariz: We have four clear priorities for our second term. First, is to build on the progress we have achieved in reducing violent crime in our city, by further reducing the homicide rate by 50 percent. We are convinced we can reach this goal by bolstering the successful strategy we have followed thus far.

Secondly, we want Sucre to have the most efficient solid waste collection system in the country. As a result, we have initiated a complex process to revamp our trash collecting system. This effort has been challenging in no small part because of the political obstacles raised by the central government against our efforts in this area. Despite challenges, we are making significant progress and are sure Sucre will be the cleanest city in all of Venezuela very soon.

Thirdly, we are about to undertake an ambitious effort to formalize land ownership for many of our citizens by granting them official deeds to their homes. We want thousands of Venezuelan families to own the homes in which they live. City Hall has been providing legal advice and support to make land ownership a reality for many of Sucre’s families. This is one area in which we do have a sharp ideological difference with the national government. We support private ownership and property as a way to create and foster wealth and progress.

Last, we will continue to develop and strengthen the participatory budget progress which has served our communities so well since being implemented.

City Mayors: Daniel Lansberg-Rodriguez described your re-election in 2013 and the support you received from middle class voters as well as from residents in the slum areas of Petare as proof that there is an alternative political model to the one provided by Venezuela’s ruling United Socialist Party. Has your re-election made a move into national politics more likely?

Mayor Ocariz: In five years we have shown clear, tangible and positive results thanks to a profound commitment to improve Sucre. We have also sought to share our experience – both positive and negative – with our fellow mayors, because at the end of the day, Venezuela will be a better country if our cities are better places to live. In the last electoral campaign, in December 2013, opposition candidates running for mayor won in 76 cities across the country. Some of the proposals advanced by opposition candidates involved emulating some of the initiatives implemented in Sucre such as how we have been able to increase revenues by making the cities tax offices closer to our communities. We have also successfully implemented digital and social media channels to improve communications and access to our residents, something that others have also sought to copy.

The quality of our service for Sucre’s residents is not tied to any political ideology. We work equally for everyone without political distinction. The central philosophy at the heart of our success is seeking to end the political polarization in our society. The best way to do that is simply by showing results. We want Sucre to be a model of excellence, results and reconciliation.

City Mayors: New York City’s most famous mayor, Fiorello La Guardia, once said: “A Mayor who cannot look fifty or seventy years ahead is not worthy of being in City Hall.” How do you see the future of Sucre?

Mayor Ocariz: I share Mayor La Guardia’s opinion.

When I started my political career many years ago, I remember a United Nations report, which affirmed Sucre was the most dangerous city in the world. It stated that of all the cities in the world, Sucre was the one where a person had the highest probability of being murdered. When I sought to become mayor and changing the difficult situation of our city, many people did not believe change was even a possibility. We have proven wrong, as evidenced by the decrease in homicide rates and other violent crime. Today, we are the municipality that most has improved in reducing violent crime. We still have much to do in this area, but our success shows that change is indeed, possible. That is why we have no doubt that in 50 or more years down the road, our municipality will be one characterized as peaceful and bursting with progress.

Sucre will be a place where the private sector is stronger, with more jobs being generated and where our citizens will not have to turn to the informal economy to make ends meet. We envision a cleaner city with more green spaces, and recreational and sporting venues. All of our citizens will be able to walk during the day and night without fear of being a victim of crime and our street, the city will be clean and our residents will be able to proudly hold title to their home.

Sucre has always been a reflection of Venezuela. Therefore, Sucre’s brighter future I foresee will be shared by a more prosperous Venezuela.

|

|

|

City Mayors: Sucre consists of some middle-class areas but also Petare, which includes Venezuela’s largest slum area. Do you find it difficult as a mayor to reconcile and serve the interests of both affluent and poor citizens?

City Mayors: Sucre consists of some middle-class areas but also Petare, which includes Venezuela’s largest slum area. Do you find it difficult as a mayor to reconcile and serve the interests of both affluent and poor citizens?