Toru Hashimoto, Mayor of Osaka

FRONT PAGE

About us

MAYORS OF THE MONTH

In 2015

Mayor of Seoul, South Korea (04/2015)

Mayor of Rotterdam, Netherlands (03/2015)

Mayor of Houston, USA, (02/2015)

Mayor of Pristina, Kosovo (01/2015)

In 2014

Mayor of Warsaw, Poland, (12/2014)

Governor of Tokyo, Japan, (11/2014)

Mayor of Wellington, New Zealand (10/2014)

Mayor of Sucre, Miranda, Venezuela (09/2014)

Mayor of Vienna, Austria (08/2014)

Mayor of Lampedusa, Italy (07/2014)

Mayor of Ghent, Belgium (06/2014)

Mayor of Montería, Colombia (05/2014)

Mayor of Liverpool, UK (04/2014)

Mayor of Pittsford Village, NY, USA (03/2014)

Mayor of Surabaya, Indonesia (02/2014)

Mayor of Santiago, Chile (01/2014)

In 2013

Mayor of Soda, India (12/2013)

Mayor of Zaragoza, Spain (11/2013)

Mayor of Marseille, France (10/2013)

Mayor of Schwäbisch Gmünd, Germany (09/2013)

Mayor of Detroit, USA (08/2013)

Mayor of Moore, USA (07/2013)

Mayor of Mexico City, Mexico (06/2013)

Mayor of Cape Town, South Africa (05/2013)

Mayor of Lima, Peru (04/2013)

Mayor of Salerno, Italy (03/2013)

Governor of Jakarta, Indonesia (02/2013)

Mayor of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (01/2013)

In 2012

Mayor of Izmir, Turkey (12/2012)

Mayor of San Antonio, USA (11/2012)

Mayor of Thessaloniki, Greece (10/2012)

Mayor of London, UK (09/2012)

Mayor of New York, USA (08/2012)

Mayor of Bilbao, Spain (07/2012)

Mayor of Bogotá, Columbia (06/2012)

Mayor of Perth, Australia (05/2012)

Mayor of Mazatlán, Mexico (04/2012)

Mayor of Tel Aviv, Israel (03/2012)

Mayor of Surrey, Canada (02/2012)

Mayor of Osaka, Japan (01/2012)

In 2011

Mayor of Ljubljana, Slovenia (12/2011)

COUNTRY SECTIONS

Argentine Mayors

Belgian Mayors

Brazilian Mayors

British Mayors

Canadian Mayors

Chilean Mayors

Colombian Mayors

Czech Mayors

French Mayors

German Mayors

Italian Mayors

Japanese Mayors

Mexican Mayors

Spanish Mayors

US Mayors

Worldwide | Elections | North America | Latin America | Europe | Asia | Africa |

|

|

Mayor of the Month for January 2012*

Toru Hashimoto

Mayor of Osaka

Profile by Andrew Stevens

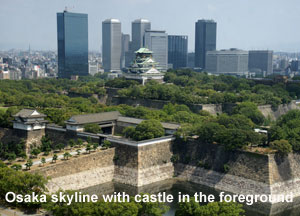

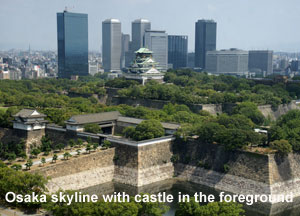

7 June 2014*: A dab hand at hogging the limelight with off the cuff and often insensitive remarks, Osaka’s youthful reformist mayor and former governor Toru Hashimoto stands apart as possibly the closest Japan has to a rock-star politician. Hashimoto’s personal crusade to consolidate the city and prefecture of Japan’s second city and commercial centre saw him become a household name as Japan’s youngest governor, until his early resignation to seek the city mayoralty in 2011. While his popularity sustained the momentum that saw his star rise to become one of the most powerful and divisive figures in Japanese politics, his frequent outbursts, particularly over victims of sexual slavery in WW2, have dented his prospects of a national role.

Update November 2015: Hirofumi Yoshimura elected new mayor of Osaka

Update October 2015: Mayor Hashimoto to retire in December.

That the flamboyant Hashimoto provides colour to an otherwise grey and lacklustre political system there is no doubt. Much has been written on his radical posture and possible threat to the existing political order, but to understand his apparent rise and status outsiders must first consider the reduced status Osaka now enjoys as the country’s once powerful commercial and industrial powerhouse, seeking to reassert itself in the global economy but considering itself hindered by unhelpful overlapping local government arrangements and wasteful bureaucracy between the prefecture and its cities. For instance, Yokohama outranks Osaka in city population terms despite being part of the Tokyo overspill. Hashimoto’s prescription of a reordered and refocused Osaka, though unpopular with the vested interests of the establishment, is an emotive and potent remedy in the eyes of city voters.

The Hashimoto phenomenon began ahead of his political career, when he became a popular television personality on a regional show offering legal advice. His media-savvy image was already tempting to Japan’s ailing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) as far back as 2007 during which time his name became banded around as a successor to the retiring governor of Osaka Prefecture, Hashimoto already having turned down the chance to run for Osaka City mayor that year. In the January 2008 poll Hashimoto took 54 per cent of the vote (against the centre-left candidate’s 29 per cent) and at 37 became the youngest governor in Japan. His rapid popularity as governor remained so pervasive that the beleaguered LDP government sought his candidature for national office ahead of its historic 2009 election defeat. However, his popularity and willingness to shatter the establishment consensus around policy saw the national political duopoly and its press sympathisers begin to turn against Hashimoto amid claims his support was somehow fabricated and his policymaking style dictator-like. The Hashimoto phenomenon began ahead of his political career, when he became a popular television personality on a regional show offering legal advice. His media-savvy image was already tempting to Japan’s ailing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) as far back as 2007 during which time his name became banded around as a successor to the retiring governor of Osaka Prefecture, Hashimoto already having turned down the chance to run for Osaka City mayor that year. In the January 2008 poll Hashimoto took 54 per cent of the vote (against the centre-left candidate’s 29 per cent) and at 37 became the youngest governor in Japan. His rapid popularity as governor remained so pervasive that the beleaguered LDP government sought his candidature for national office ahead of its historic 2009 election defeat. However, his popularity and willingness to shatter the establishment consensus around policy saw the national political duopoly and its press sympathisers begin to turn against Hashimoto amid claims his support was somehow fabricated and his policymaking style dictator-like.

As governor of the Osaka Prefecture, Hashimoto quickly moved on from his early beginnings as a typical local administrator backed by the hegemonic LDP into the figurehead of his own regional political bloc ‘One Osaka’. Ostensibly One Osaka’s primary goal is the realisation of Hashimoto’s signature policy of a consolidated merger between Osaka Prefecture and its constituent cities, including Osaka itself but also the neighbouring ‘designated city’ of Sakai. But the party has also sought to provide a distinctive platform around education reform, seeking to emulate the Thatcherite reforms of 1980s Britain where stronger standards and local autonomy were encouraged. Such policies are anathema to Japan’s education ministry, which prizes the substantial levers of control it retains through the channelling of national subsidies to largely supine local boards of education.

As a result of the country’s on-going nuclear crisis following the events of 3/11, Hashimoto also used his party’s regional influence to assert One Osaka’s stance against reliance on nuclear energy, spying the votes available in being willing to take on the faceless regional energy monopoly KEPCO. One Osaka’s policy of promoting more localised and alternative energy sources has set it on course for a clash with the once powerful but discredited energy giant, albeit with massive public support for the policy.

Hashimoto’s decision to quit the governorship early in order to seek the Osaka mayoralty and realise One Osaka’s vision, although not unexpected, was criticised for its timing. In standing down ahead of the 2012 gubernatorial elections, Hashimoto’s standing in November 2011 against the incumbent Osaka mayor Kunio Hiramatsu was brushed off by One Osaka as unavoidable given the election scheduling. Others pondered why Hashimoto, at the height of his powers as the executive of a prefecture of 8.9m people and sought out for national office, would settle for being a “mere mayor”. In the event, a highly polarised city race which became a national event ensued, with the incumbent ‘fuddy-duddy’ Hiramatsu supported by all the main parties but forced on the back-foot against the momentum of One Osaka, which took not only the mayoralty but retained the governorship on increased turnouts and by substantial margins (59 and 54 per cent respectively). The enviable mandates of Hashimoto and his One Osaka ally Ichiro Matsui, now governor, were keenly studied and felt in the capital Tokyo as national politicos prepared themselves to cope with the reality of both local government reorganisation and national political realignment at the behest of jaded voters.

Inevitably perhaps, those cities, which would be absorbed into a unified single-tier Osaka, such as neighbouring Sakai, do not view their mooted disappearance with much sympathy. But amid economic slump, Hashimoto and his allies are able to easily portray such resistance to their proposal as romantic attachment to old administrative boundaries, which fly in the face of economic reality and rest on the cosy consensus-orientated establishment thinking, which avoids difficult decisions and stifles leadership. The prize, as they see it, is Osaka’s emergence as a significant metropolis amid the Tokyo-Nagoya-Osaka mega-region globally and as part of a Kansai megalopolis of 20m people within Japan, whose economy is as significant as that of regional competitors such as Singapore. However, the current set-up sees much duplication and waste among constrained administrative units, which views the city of Osaka as just one of several ‘municipalities’ in the prefecture.

Such resolute leadership in a system, which prizes modest effort and consensus is not appreciated by everyone. During the election, Hashimoto’s opponents coined the phrase ‘Hashism’ as a play on his surname and autocratic tendencies. Hashimoto has also, by his own actions, drawn comparisons to his elder counterpart (now party co-leader) Shintaro Ishihara in Tokyo, who has spoken glowingly of his protégé. As governor, Hashimoto closely emulated Ishihara’s combative stance on constitutional issues, disciplining teachers who failed to stand for the national anthem at ceremonies and even taking a revisionist approach to wartime atrocities. Negotiations between Hashimoto and Ishihara following the 3/11 earthquake and tsunami saw a joint plan for Osaka to become a ‘back up’ capital for Japan amid any future emergency, which may devastate Tokyo. Since then, their political cooperation has deepened, with Ishihara seeking support for his own new rightist party, while backing Hashimoto's newly created Nippon Ishin no Kai (Japan Restoration Party) which aimed to dislodge vulnerable legislators in the December 2012 general election. Having already secured a new law to begin the process of streamlining his metropolis, Hashimoto's new party goes beyond the aims of One Osaka, seeking sweeping constitutional reforms such as abolition of the upper house of parliament, a directly elected prime minister and radical regional decentralisation.

Hashimoto’s appeal as an outsider was further underscored by revelations, which emerged during the mayoral election, when it was revealed that his biological father was a member of an organised crime syndicate. Although once unthinkable perhaps, in a system populated by dull technocrats or scions of wealthy dynasties, such revelations merely served to embolden his earthy electoral appeal, not least as the resources of the establishment being pitted against him ultimately played well with city voters. In any case, the mayor is the father of seven children, having met his wife in high school, as far from the gangster image as could be (although in June 2012 he admitted to an extramarital affair before becoming governor).

Not long after his election Osaka’s mayor picked a fight with city labour unions, pledging to remove them from the city hall and tackle incompetence among 'job for life' bureaucrats, as well as push through radical (by Japanese standards) plans to privatise the city transport system. Having failed to produce the knock-out blow to Japan’s main parties in the 2012 general election, the Ishihara-Hashimoto project rumbled on regardless, eying the following summer’s upper house elections as the next event in their bid to ‘restore’ Japan. Remarks in May 2013 concerning the use of sexual slavery in Japanese occupied territories during WW2 (so-called ‘comfort women’) and the “sexual energy” of US forces based in modern-day Japan plunged the newly gaffe-prone Hashimoto into a PR quagmire, leading to plummeting personal ratings in political opinion polls. Boycotts by US mayors followed and have led some to speculate that Hashimoto’s waned star has led the mayor to seek a political exit in a blaze of glory in order to cash in on his celebrity status while he is still young.

May 2014 saw an eventual parting of the ways between the Osaka mayor and Tokyo's Ishihara, as their nationalist party decided to demerge between the two city factions.

*This article was originally published in January 2012 and updated in August and September 2012, in July 2013 and again in June 2014.

|

|

|

The Hashimoto phenomenon began ahead of his political career, when he became a popular television personality on a regional show offering legal advice. His media-savvy image was already tempting to Japan’s ailing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) as far back as 2007 during which time his name became banded around as a successor to the retiring governor of Osaka Prefecture, Hashimoto already having turned down the chance to run for Osaka City mayor that year. In the January 2008 poll Hashimoto took 54 per cent of the vote (against the centre-left candidate’s 29 per cent) and at 37 became the youngest governor in Japan. His rapid popularity as governor remained so pervasive that the beleaguered LDP government sought his candidature for national office ahead of its historic 2009 election defeat. However, his popularity and willingness to shatter the establishment consensus around policy saw the national political duopoly and its press sympathisers begin to turn against Hashimoto amid claims his support was somehow fabricated and his policymaking style dictator-like.

The Hashimoto phenomenon began ahead of his political career, when he became a popular television personality on a regional show offering legal advice. His media-savvy image was already tempting to Japan’s ailing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) as far back as 2007 during which time his name became banded around as a successor to the retiring governor of Osaka Prefecture, Hashimoto already having turned down the chance to run for Osaka City mayor that year. In the January 2008 poll Hashimoto took 54 per cent of the vote (against the centre-left candidate’s 29 per cent) and at 37 became the youngest governor in Japan. His rapid popularity as governor remained so pervasive that the beleaguered LDP government sought his candidature for national office ahead of its historic 2009 election defeat. However, his popularity and willingness to shatter the establishment consensus around policy saw the national political duopoly and its press sympathisers begin to turn against Hashimoto amid claims his support was somehow fabricated and his policymaking style dictator-like.